|

|

|

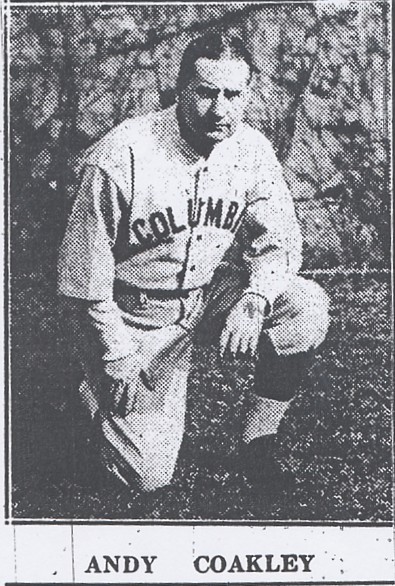

"MAJOR LEAGUE STARS WILL COACH VARSITY", read the he headline of the February 18, 1914 issue of the

Columbia Spectator. That day, Columbia University announced it had made a radical move: it had hired not one, but two

men to split the coaching responsibilities on the baseball team, "in an effort on the part of the baseball management

to assure a winning team for Columbia," the Spectator said. Former outfielder Billy Lush, who had spent several seasons at Yale and coaching minor league teams, would be the "supreme head of the team", while

Andy Coakley would be in charge of developing pitchers and catchers.

|

|

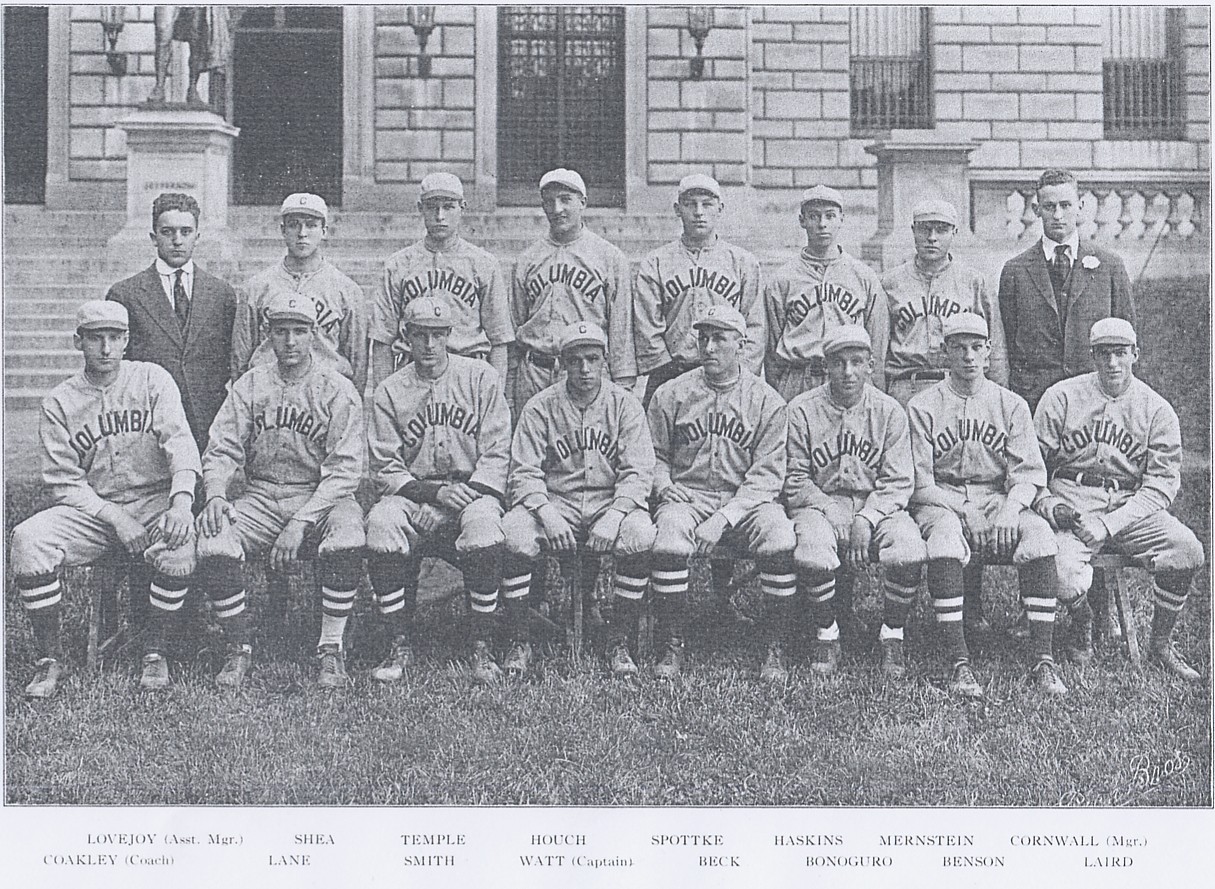

| Coakley's "Greatest Team", the 1916 Columbia Lions |

|

| The Columbian, 1918 |

The Columbia Lions of 1914 -- a team devoid of many of its starters from the season before -- performed respectably,

going 10-7. Coakley received particular recognition for the development of rookie Eddie Shea, who became one of the best collegiate

pitchers in the East that spring. But Coakley's contract ran out at the end of the season. Perhaps fearing he would not

be re-signed, he bought the a baseball franchise within the Atlantic League, and became its manager, captain, and ace pitcher

that summer, spending less time in Morningside Heights as the season wore on, and more time with his ballclub in Asbury Park.

| Andy Coakley as Columbia Coach |

|

| Columbia Spectator file photo |

But the time Coakley did spend as pitching coach at Columbia, his players had taken quite a liking to him, and following

the end of his season, the 1914 Lions presented him with an appreciative trophy cup. As it turned out, Columbia would not

renew Lush's contract for another season, and by November 20, 1914 -- Coakley's 32nd birthday -- the Lions' ex-pitching coach

had been promoted to head coach to start 1915.

In 1916 -- just Coakley's second season -- it all came together. For years afterwards, Coakley would still refer to his

team that year as the greatest he had ever coached, "as it was the first and only team in which I

could employ major league tactics," he said. Nearly every player had the talent to play professionally that year,

and three -- secondbaseman and captain Bobby Watt, shortstop Mike "Bunny" Buonoguro, and pitcher George Smith -- were offered major league contracts at the end of the season. (Though only Smith accepted.)

The Lion nine that season went a stunning 17-1, losing their only contest 3-0 to the Poughkeepsie Cubans early in the

season. Their defining game came perhaps on June 3, when Smith pitched a 1-hitter against Stevens tech for the 7-0 win, and

leftfielder Reynolds Benson hit two homeruns. 1916 also marked the first year that Columbia played two opponents on the same

day; the May 30 doubleheader had become necessary because of earlier-season rainouts, and the Lions took both ends -- 11-0

over Lafayette and 4-1 over NYU.

What was Coakley's method of training that had fostered so much talent so quickly? His seasonal training routine was

somewhat straightforward. The team would begin indoor practice in early February -- at first just throwing and other conditioning

exercises, but by mid-March, the players were practicing out of a batting cage in the gym.

"The first thing I notice about a player is how he throws," Coakley told the

Spectator on March 28, 1947, "To a ball-player, a man must have a good arm. Once I've been satisfied as to

a man's throwing ability, I carefully watch his batting form. it's impossible to determine whether or not a man is a good

hitter, but I can tell with just one swing whether a man is not [a] hitter at all. Any batter that stands in the box with

his stomach and gut sucked in cannot possibly be a hitter. A man has to stand at the plate with his body relaxed. Any man

that possesses a fear of being hit is just not a big leaguer. A ball player should have enough confidence in his own reflexes

to not even consider the possibility of being hit by a pitch."

Around the time Coakley would start making cuts from the team, the weather would warm up enough that the players could

start practicing outside -- up until 1924, that meant South Field, the area between 115th and 116th street including where

Butler Library stands now on Columbia's campus; after 1924, the team moved uptown to the diamond on Baker Field where it still

plays today. Until the start of the season during the first week of April, the Lion nine would practice drills and play scrimmage

games.

In 1917, with the start of World War I imminently around the corner, military training drills were added as a mandatory

part of the workout routine, in the advent of a draft. They would last throughout the duration of the war.

| Coach Coakley promotes Colgate Ribbon Dental Cream |

|

| http://www.goantiques.com/detail,colgate's-ribbon-dental,146347.html |

During the early season games, Coakley tended to experiment with his lineup -- mix around batting orders, start different

players at different positions, fiddle with the pitching rotation -- in order to determine the best nine guys

to start once the conference schedule began. The Eastern Intercollegiate Baseball League, out of which Columbia played during

the Coakley era, formed in 1930; prior to it, the Lions had played in a somewhat less formal Quadrangular League with

four of its current Ivy opponents.

In 1920, the Lions won eight straight games, but the decade, for the most part, saw Columbia as a collective team mired

in mediocrity. One of the few bright spots was, of course, Lou Gehrig, who enjoyed a short, but unforgettable, 19-game stint with the Columbia nine in 1923.

Coakley preferred not to impose rigid training restrictions on his players-- according to the New York

Times on September 28, 1963--because he felt that the more rules he created, the more useless they would become in that

they would not be enforced. "The worst thing they do is drink too many ice cream sodas,"

Coakley lamented once on his loose system. His laxness and casual authority allowed him to develop a close relationship with

many of his players over the years, many of whom kept in touch long after graduation.

The 1932 team set a modern varsity record on April 29 that still stands today when they scored 27 runs against Cornell,

but it was the 1933 team that brought home all the glory to Columbia. The "Coakleymen" -- as many print sources referred

to them -- won their first EIBL Championship that season. Pitcher Ray White, who was signed to the New York Yankees' minor

league system afterwards, was the captain.

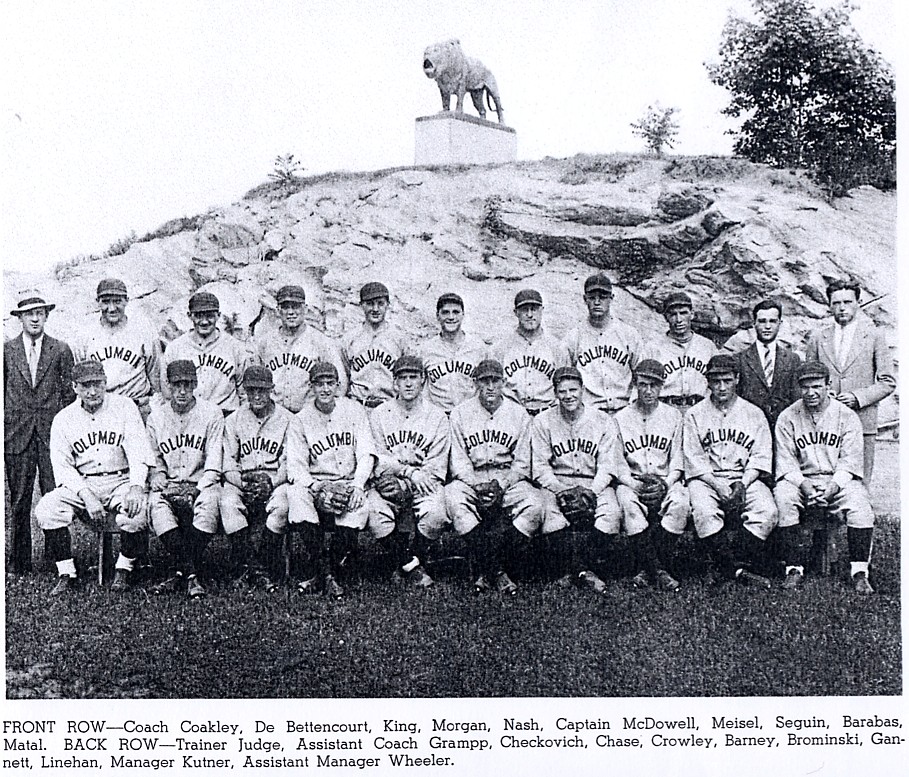

| The EIBL Champion 1934 Columbia Lions |

|

| The Columbian, 1935 |

But the prospects for success at the dawn of the 1934 season were somewhat mixed. The "core" of the 1933 squad was still

intact, despite the loss of White, but the team had been hampered by bad weather during the first few weeks of the season,

and did not play a full game until April 19, which they lost, 9-8. The Lions, in fact, would drop four of their first five

games that year. Then they went on a tear, capturing their next seven straight. By the end of the season, they had secured

another league title -- back-to-back first place finishes. Columbia led the league in "every department except pitching,"

the 1935 Columbian said. The team topped the league in runs scored, RBIs, and hits, as well as set what was then

an Eastern League record when they collectively clouted ten homeruns against conference rivals. Defensively the Lions were

also solid, leading the league in double plays and chances.

In 1939, Coakley's Lions put themselves in the books by becoming the first sporting event on television, when

they hosted a doubleheader against Princeton on May 17. Hector Dowd, the pitcher, hurled the complete, 10-inning second game,

but Columbia would lose to Princeton, ultimately, 2-1, as well as drop the first game 8-6 to the Tigers.

| Baker Field during the first televised game, 1939 |

|

| http://www.college.columbia.edu/cct/spr99/34a.html |

He coached summer collegiate ball at Columbia, as well, in 1943. The team played once a week, and involved most

of the regulars from the spring season. In June of 1944, however, pressured by commuting costs of bringing the squad to and

from Baker Field as well as Columbia's eagerness to get an early start on the fall football season, the college

discontinued its summer leagues -- following the trend of many of its summer rivals, who did it, in part, because the number

of players lost to the war effort.

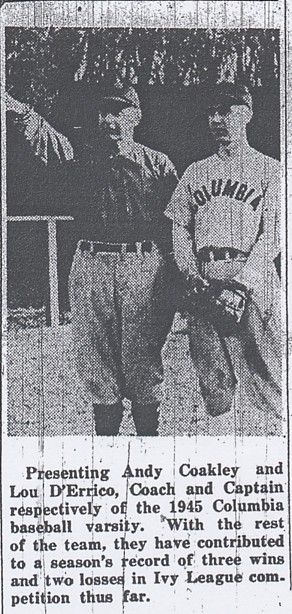

| Coakley instructing 1945 captain Lou D'Errico |

|

| Columbia Spectator 6/15/45 |

|

|

LIFETIME COACHING RECORD WITH COLUMBIA (including

1914)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|