|

|

|

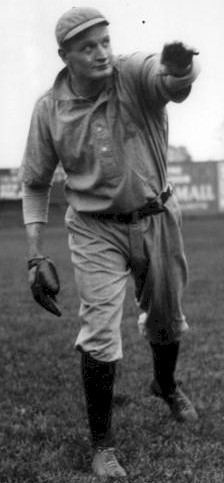

Andrew James Coakley, who was born in Providence, R. I. on November 20, 1882, first developed into standout

pitcher at Providence High School. Despite being tall and ungainly -- 6'0" and 145 lbs. -- he possessed a killer fastball

and curveball, that, while he was attending college at Holy Cross around the turn of the century, established him as one of

the top amateur pitchers in the country. His string of shutouts -- including a particularly impressive 1-0 eleven-inning victory

over Yale -- attracted the attention of the Philadelphia Athletics, who signed him in 1902. Thus, Coakley became

one of only a handful of players to go straight from amateur baseball to the major leagues without being farmed out to the

minors first.

|

|

| A young Andy Coakley c. 1906 |

|

| http://www.kenji-usa.com/HTML/ Theshrine/oldphotos/phillie_athletics.htm |

Athough he had not yet graduated college, Coakley joined the Athletics' roster in the fall of 1902, and made his

major league debut against the Washington Senators on September 17 under the alias "Jack McAllister." According to the Columbia

Spectator on March 26, 1947, the 19-year-old hurler "was so fast that day and so deceptive" off the mound that the

Senators staff attempted to steal Philadelphia's signals. Coakley and Ossee Schreckengost, the catcher, discovered what the

Senators had been doing, and quickly met and secretly changed their signals. When the Senators' third base coach tipped

off to the very next batter, Washington's Bill Coughlin, what the next pitch would be, Coughlin prepared to swing at a curveball.

But Coakley threw a fastball on the inside of the plate, and Coughlin, who had been waiting for the ball to break, was hit

square in the jaw -- "breaking the bone and sending all of his teeth flying toward the stands!!!" the Spectator colorfully

recounted. Coakley would end up winning his first game in the bigs, and would make two more appearances for the A's that season

-- totalling a 2-1 record and a 2.67 Earned Run Average.

But Coakley -- who the next spring began using his birth name -- would not be able to reprise his rookie

success the following season. He did not win a single game in 1903 and posted a 5.50 ERA, and over the course of

that season and the next he experienced a tough time cracking the Athletics' pitching rotation, littered with such big-names

as future Hall-of-Famers Rube Waddell, Chief Bender and Eddie Plank.

In 1905, however, Coakley finally broke through, posting a record of 18-8 (though early sources claim he went 20-6

that year), with a league fourth-best 1.84 ERA and league ninth-best 145 strikeouts. His accomplishments, however, were

somewhat overshadowed by those of Rube Waddell, who was also having a career year, as the Athletics ace finished atop the league in wins, strikeouts, and

ERA to win the pitching Triple Crown. The Athletics captured the American League pennant that year, and went on to face the

New York Giants in baseball's second World Series, where they lost, four games to one.

But it was in the 1905 World Series that Coakley experienced what he would forever after consider his "greatest thrill" -- pitching against the legendary Christy Mathewson in the Game 3. Burned by five errors from his teammates in the field -- four of which came on double play balls -- that

let in seven unearned runs, Coakley got pegged somewhat unfairly with the 9-0 loss. Years later, Coakley would admit that

he felt he had been hardly effective -- he'd given up eight hits and walked five -- that he had lost some of his intensity

from having had to warm up and prepare to pitch the game a day earlier, before rain postponed his start until the following

afternoon.

Mathewson, on the other hand, had been brilliant throughout the entire series, as he would become the

only pitcher ever to record three complete-game shutouts in one Fall Classic. The day he opposed Coakley on the mound, he blanked

the A's with just four weak hits and a hit batsman -- Coakley, whom Matty plunked on the arm during an at-bat.

| Rube Waddell |

|

| http://www.baseballhalloffame.org/ hofers_and_honorees/wallpaper/ waddell_rube.jpg |

Interestingly enough, Coakley might never have gotten to pitch during the Series if not for a bizarre incident between

him and Waddell in September 1905, at the close of the regular season:

"Rube loved antics," Coakley said. "This particular day he was bashing

in his teammates' straw hats. He had been pretty successful, and now attempted to gain mine as a trophy. I couldn't afford

to buy too many hats at the time and I hid it behind my back. Well, as he lurched for it, the grip I was carrying accidentally

hit him a solid blow on the shoulder. It kept him out of action for the rest of the season and also out of the World Series

against the Giants.

"But Rube, although he could probably tell on the spot that the

blow would be of consequence, wasn't one to hold a grudge.

"'Why don't you kiss and make up with Andy,' somebody suggested.

"'Hell, sure I'll make up with him,' Rube said, 'but I'll be damned

if I'll kiss him!'"

The injury Coakley had inadvertently dealt Waddell had enabled the junior pitcher to become the replacement third

starter in that year's Fall Classic.

Unfortunately, Coakley would never quite see the same success as a ballplayer as he experienced in 1905 again. He went

7-8 with a 3.14 ERA in 1906, pitching just slightly more than half the amount of innings he had thrown the previous season.

More significant about 1906, though, was an event that took place outside of the ballpark, one that demonstrated his

keen eye for talent even then, and perhaps foreshadowed things to come during his post-playing days. 1906 was the year

Coakley married Martha Gray--to whom he would stay married until his death, in 1963--and Athletics manager Connie Mack urged him to take some time off during the season. So Coakley took his new bride to Vermont for a week, where he noticed a

shortstop working out with a semipro club -- named Eddie Collins. Impressed with the youngester's abilities, Coakley notified Mack of the find immediately, and Collins was playing for the

Athletics before the season's end. Interestingly enough, Collins -- who would be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame after

a 25-year career in the bigs --had been attending Columbia University at the time, and, as he would return to Columbia that

fall to finish off his degree, his professional status was ruled him ineligible to play collegiate baseball in 1907,

his senior year. (While coaching at Columbia in 1921, Coakley would fight a similar issue regarding Lou Gehrig playing professionally -- from the other side, of course.)

| Baseball Hall of Famer Eddie Collins, CC '07 |

|

| http://www.cmgww.com/baseball/collins/image3.jpg |

On December 13, 1906, the Athletics sold Coakley to the Cincinnati, where he would spend nearly the next two

seasons. In 1907, he went 17-16 for the Reds with a 2.34 ERA. An interesting sidebar to Coakley's career happened during a

game on June 18 of that year, when he hit Giants catcher Roger Bresnahan in the head with a pitch, knocking him unconscious. Feared dead, Bresnahan was given his last rites while he lay on

the field. While he spent the next ten days in the hospital, Bresnahan would develop what was perhaps the first batting helmet,

though he himself would not wear it upon his return to the field on July 12 -- in another game against Coakley and the Reds.

Bresnahan (whom Coakley would later put on his All Time Team), would collect two hits that day off Coakley, who would be pegged with the 3-2 loss.

1908 was marked by hard luck -- namely, several faceoffs against ex-World Series rival Christy Mathewson. On May 16, Coakley would get revenge for the 1905 World Series, twirling a six-hit, 6-1 victory against the Giants

-- a game in which Matty was sent to the showers after two innings. But Matty would win the other battles. On June 17, the

future charter Hall of Famers took the opener of a doubleheader from Coakley and the Reds, 2-1. On July 6, he beat Coakley

again by the same score. During an August 4 doublheader, Mathewson would factor as the victorious pitcher in both games, winning

the first one in relief -- 4-3 in 12 innings -- and the second in a nine-inning 4-1 complete game of his own; on both ends,

Coakley was also the losing pitcher. Two weeks later --August 20 -- Mathewson would hurl a 2-0, 8-hit shutout against Coakley...

despite Coakley only allowing four hits the entire nine innings.

The incessant number of near-misses against Mathewson's Giants were quintessential examples of a year in which Coakley

would pitch well, but struggle for run support from the hapless Reds. On September 1, he had a miniscule 1.86 ERA with

a disappointing 8-18 record when he was sold to the Chicago Cubs, who were in the midst of a pennant race. Coakley would start

three games for Chicago that September -- winning two, to finish the year 10-18 with a 1.78 ERA -- as the Cubs, powered

by pitching ace Mordecai "Three-Finger" Brown, and the immortal double-play combination of Tinker-to-Evers-to-Chance, would win their third consecutive National League Pennant. Though Coakley did not pitch in the 1908 postseason, he was on

the bench as the Cubs captured what would be their last World Series.

| Frank Chance, Joe Tinker, Johnny Evers |

|

| http://pro.corbis.com/images/watermark/67/12394482/VV10144.jpg |

Contract trouble would lead to Coakley's demise, however; it sidelined him for almost the entire 1909 season with the

Cubs. Ultimately, he would pitch a single game for them that year, allowing four runs in just two innings to pick up the loss.

He did not pitch at all in the majors in 1910.

Coakley began to explore other options during this idle period, including coaching the Williams College baseball

team in the spring of 1911. But he missed pitching, and, following the end of the collegiate season, Coakley attempted a short-lived

comeback with the New York Highlanders (later Yankees). After just two appearances on the mound, he suffered a debilitating

injury to his thumb, which would mark the end of his pitching career; Coakley's days as a professional ballplayer were over.

<b>See Andy Coakley's career major league statitstics</b>

Coakley returned to Williams for the 1912 season, to coach a team that, according to the Spectator on February

18, 1914, "defeated practically every strong college team in this part of the country." The ace of the Williams rotation that

year was right-hander George Davis, who went on to a four-year professional pitching career with the Highlanders and the Boston Braves. The following season,

1913, Williams was "the team that stopped Yale, after the Elis had threatened to break all records for consecutive victories."

But then there was, what the Spectator called, a "change of policy" at Williams, and Coakley suddenly found

himself a "free agent."

Columbia University came calling.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|